- Benchmark Education

- Newmark Learning

- Reycraft Books

- Create an Account

The Science of Reading is ever-evolving.

While the Science of Reading is not new, a heightened awareness of the cognitive processes involved in learning to read has led to important changes—in phonics instruction, knowledge building, and teacher professional development— all greatly benefiting students.

But it has also led to some misconceptions and overgeneralizations. There remains much to discover about learning to read. And as we gain insight, it’s important that we expand the conversation, approaching the Science of Reading with a broader 360° view—valuing current understandings, but also considering the nuances of teaching and learning literacy in today’s classrooms.

There is much we do not know and there is a lot [yet] to learn.

—Emily Hanford,

Sold a Story

Our 360° View of Literacy Incorporates Five Evidence-Based Fundamentals:

1

_____

Teaching and learning must be informed by validated research.

2

_____

Learning to read involves many connected cognitive processes.

3

_____

Literacy proficiency requires an integration of reading, writing, speaking, listening, viewing, and engagement.

4

_____

The unique needs of all learners are at the center of teaching and learning.

5

_____

Professional learning and usability are top priorities.

1. Validated Research

Research in education is now informed by many fields of science, including linguistics, neuroscience, and cognitive psychology. Understandings of how humans learn to read and write and how this knowledge translates into instruction continue to evolve.

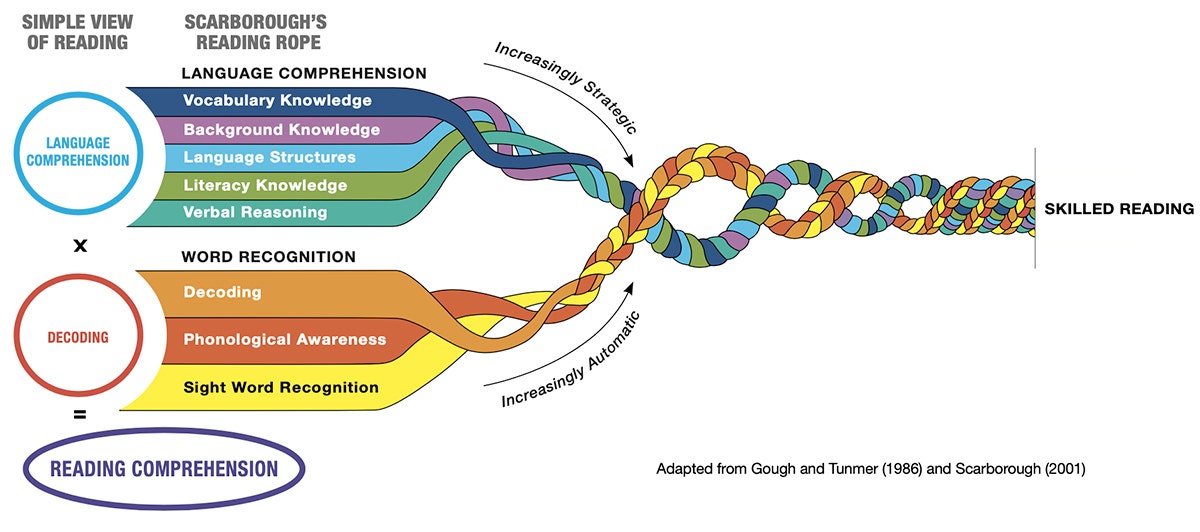

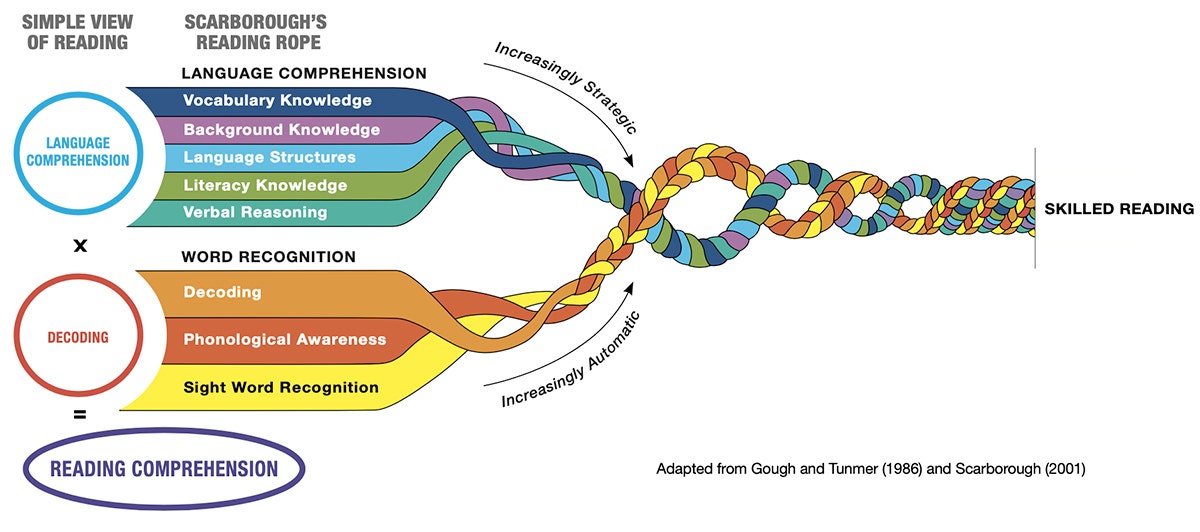

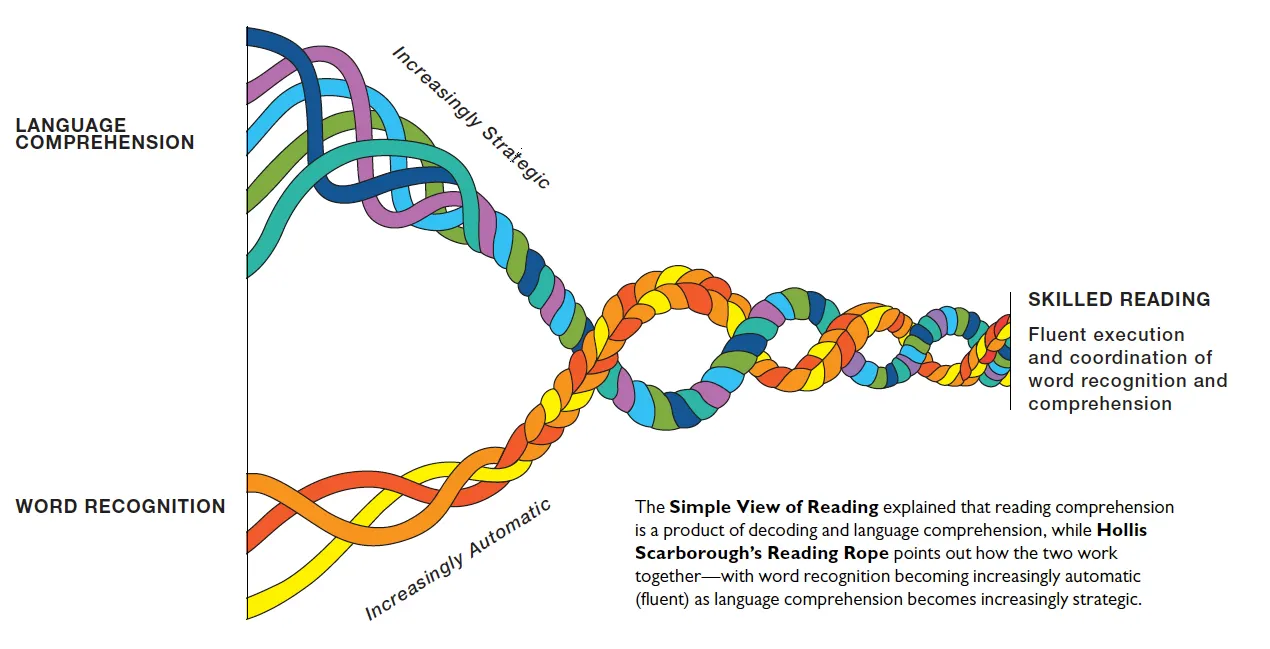

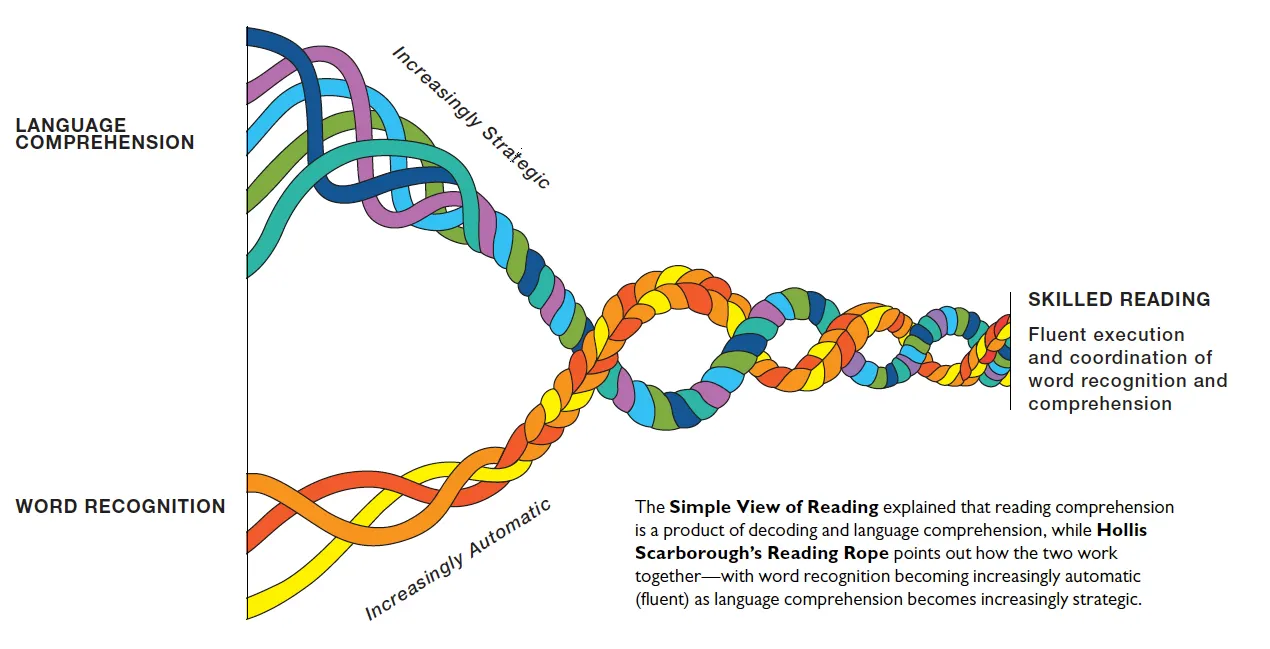

The Simple View of Reading and Reading Rope models help situate phonics in its proper place while emphasizing that phonics alone is not enough to achieve skilled reading.

Classroom

Applications

Keep these reading models in a place where you can see and reference them often. Being familiar with the brain processes involved in reading will help as you work with your students and identify instructional next steps.

Ensure your reading instruction addresses all the areas identified in these models. Some areas will need more focus depending on your students’ age and reading development.

In the Simple View from Philip Gough and William Tunmer, reading comprehension is a product of decoding and oral language comprehension: successful decoding allows print to be translated to oral language, and listening comprehension ability then determines comprehension.

Scarborough’s Reading Rope summarizes what was understood about the component parts of decoding and comprehension—seen as two strands of rope that twist together to become reading, with the skills and knowledge of each section listed. Included was the necessity of automaticity for decoding skills and strategic intention for comprehension.

The Active View of Reading model from Nell Duke and Kelly Cartwright goes a step further to show the important aspects of reading development that overlap—vocabulary, morphological awareness, and fluency, serving as a bridge between Word Recognition and Language Comprehension—and the role of active self-regulation, including executive function and motivation, in governing the process.

Classroom

Applications

Form a Science of Reading Book Club to learn and share knowledge. See our Resources and References to get started.

Common Misconceptions

The Simple View, the Reading Rope, and the Active View are all models of reading, not of reading instruction or learning to read. They describe the process of reading and the abilities one must marshal to read, but they have little to say about what a school district or teacher needs to do to raise reading achievement.

Research in education is now informed by many fields of science, including linguistics, neuroscience, and cognitive psychology. Understandings of how humans learn to read and write and how this knowledge translates into instruction continue to evolve.

The Simple View of Reading and Reading Rope models help situate phonics in its proper place while emphasizing that phonics alone is not enough to achieve skilled reading.

Classroom

Applications

Take advantage of professional learning opportunities offered by your school and from trusted literacy experts.

Common Misconceptions

Contrary to popular belief, there is NO research that says decodable texts must be 100% controlled for phonics, but there IS research that warns against using decodability as the only criteria. A majority of words should be decodable, but highfrequency words and academic vocabulary must also be included to create stories that are sensible and engaging.

Validated Research: THEORY INTO ACTION

Research-Based Foundational Skills Routines

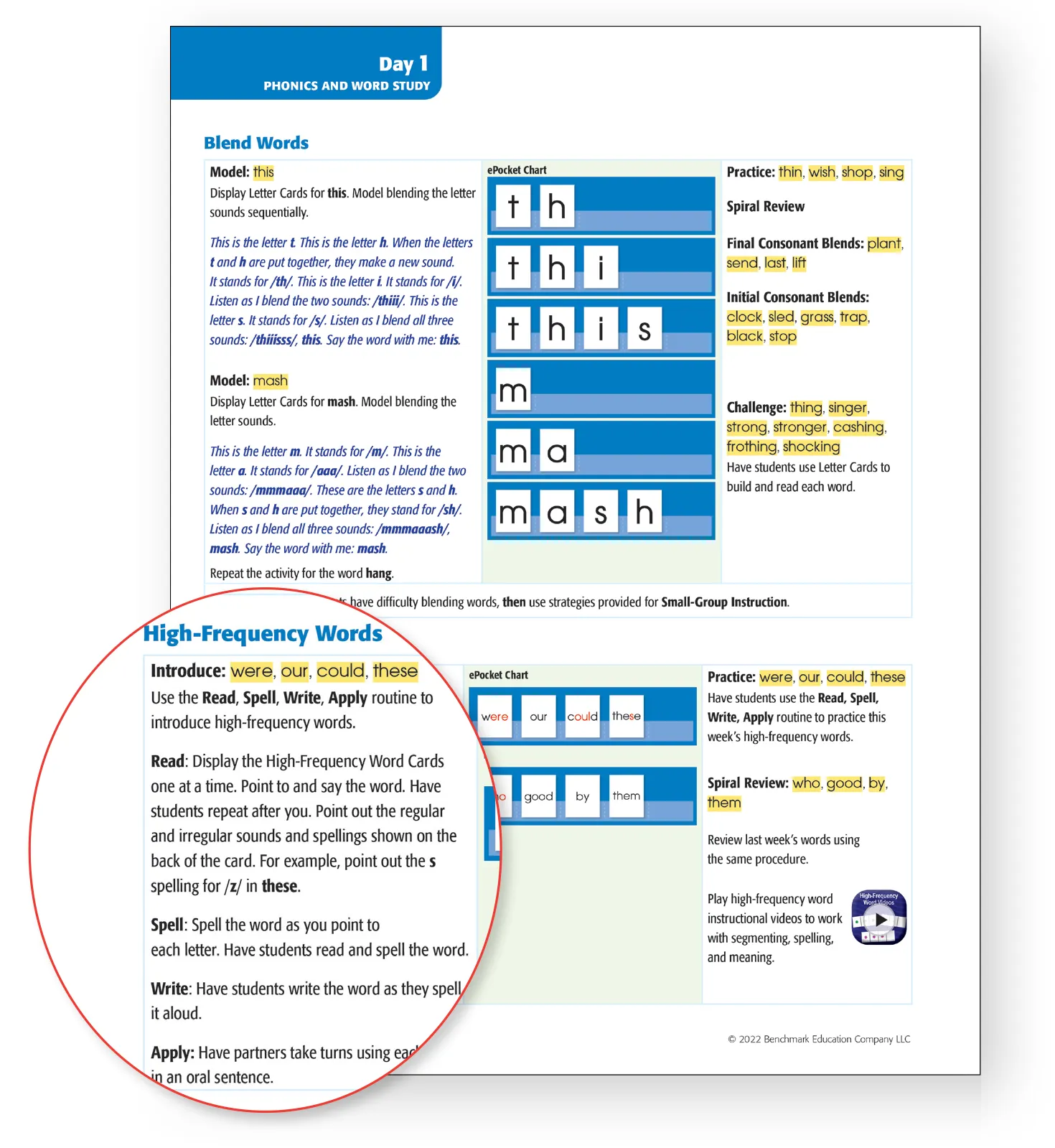

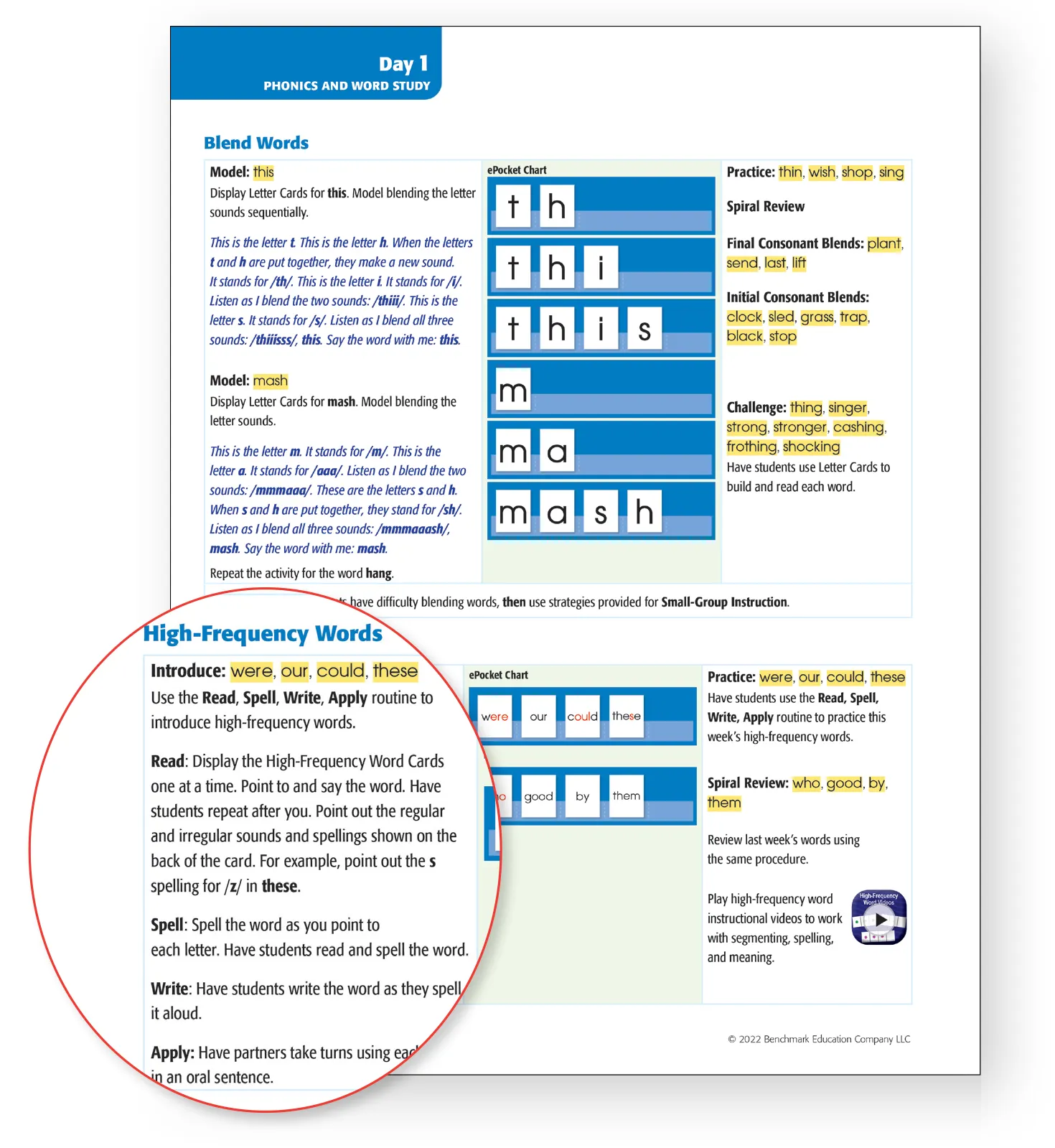

High-frequency word routines should be embedded in foundational skills instruction. These routines should promote orthographic mapping, where it is necessary to attend to the individual sounds and their spellings in the word, even when irregular. This is in stark contrast to a whole-word approach.

High-frequency word routine:

- READ: Students attend to individual sounds in the word, noting irregular sounds.

- SPELL: Students spell the word as the teacher points to each letter

- WRITE: Students encode the word as they spell it aloud, attending to individual sounds.

- APPLY: Students use the word in an oral sentence, reinforcing meaning.

Source: Benchmark Advance, Grade 1 phonics lesson

2. Connected Cognitive Processes

Reading in English does not develop in the same way that language does (Moats & Tolman, 2009). Instead, it is a highly complex learned human behavior that for many requires code-based, explicit instruction (Young, 2023).

It is not enough to bring strong language comprehension skills to a text and assume comprehension will naturally follow. Conversely, automatic and accurate decoding without sufficient language comprehension will not prove effective.

Reading is more than sounding out words.

—Wiley Blevins

Classroom

Applications

According to phonics expert Wiley Blevins, at least 50% of a phonics lesson should be spent in application. That’s where the learning sticks.

Not all decodables are created equal. Ensure your decodable texts are instructive, comprehensible, and engaging, offering teacher support and family involvement.

Teach rich, content-area vocabulary explicitly to students and offer multiple exposures to these words in texts students read, listen to, and respond to.

Reading is a process of connected skills: language comprehension skills, decoding skills, knowledge building, and metacognitive behaviors and mindsets, including motivation and engagement, comprehension monitoring, and the executive functions of self-control, organization, memory, and time management.

Common Misconceptions

Some have assumed that since the Reading Rope graphic begins with separate word recognition and language comprehension strands, reading instruction should isolate word recognition (decoding) and language comprehension lessons. However, that approach is not always appropriate. In fact, students’ study of the word recognition aspect of the rope can relate to the language comprehension portion and to building knowledge.

Reading comprehension is generally understood to be a prerequisite to fluency. In fact, fluency also supports comprehension.

Proficient reading requires that the ‘strands’ associated with language comprehension and word recognition work seamlessly together in the brain’s processing systems.

—Moats, 2020;

Dehaene, 2009, 2013

Current and confirmed research points to other considerations that play a significant role in reading acquisition and teaching— for example, knowledge building. When knowledge building is prioritized, often through the adoption of content-rich literacy curriculum, vocabulary increases and reading comprehension improves (Davidson & Liben, 2019).

Another example is the role of metacognitive behaviors and mindsets such as executive functioning, comprehension monitoring, mindfulness, and motivation. According to Dr. Peter Afflerbach (2023), metacognition is the “awareness of own’s own knowledge…and the ability to understand, control, and manipulate one’s cognitive processes” (p. 10). A lack of attention to this keeps students relying on the feedback of others, lessening reading independence.

Together these processes, and others, form intricately connected roots that grow into a solid foundation for reading proficiency.

Knowledge building involves an emphasis on supporting understanding of big ideas and important concepts through extended reading and other experiences.

—Cervetti & Hiebert,

2019

Connected Cognitive Processes: THEORY INTO ACTION

Connecting Knowledge Building and Phonics

Instruction in foundational skills and knowledge building instruction do not have to happen in isolation. Find ways to integrate knowledge building into your foundational skills instruction!

Some curricula overemphasize phonics isolated skill work, while ignoring other key aspects of early reading needs (e.g., vocabulary and background knowledge building) that are essential to long-term reading progress. These skills plant the seeds for comprehension.

Ways to connect instruction across phonics and knowledge building:

- Use decodable texts and passages that also build knowledge in the content areas.

- Organize your instructional units around content-rich topics and teach vocabulary .

Source: Benchmark Advance, My Reading and Writing student accountable texts, and BEC Decodables aligned to unit topics

3. Integrated Literacies

Skilled reading is just one piece of what it means to be literate today.

Integrated skill in reading, writing, speaking, listening, and viewing positions students to meet challenging and changing societal and economic demands (Darling-Hammond, L., Schachner, A. & Edgerton, A.K., 2020).

All students need structured opportunities for expressive language use—writing and speaking—that is grounded in meaningful, authentic text every day. And because these literacies closely inform and influence one another, integration can be motivating and fun for students.

Classroom

Applications

Structure your classroom culture and environment so that students have multiple opportunities each day to talk and write with peers in collaboratively constructing meaning about texts.

In preparation for reading a complex text, use videos and images to build knowledge, student motivation, and vocabulary—students can be asked to discuss or write about what they have viewed (Sedita, 2023).

To be fully literate, or to communicate effectively and make sense of the world, individuals need to be skilled readers, writers, and communicators with adequate speaking, listening, and viewing skills.

—Common Core Standards, 2010; Graham, 2020;

Lankshear & Knobel, 2007

When students respond to text through writing, there are multiple benefits. They gain a deeper understanding of the text while also building content knowledge, critical thinking, and an integration of comprehension and writing skills.

Responding to text in writing has been shown to support comprehension, for both students in general and students who are weaker readers or writers in particular. This applies across expository and narrative texts as well as in content areas such as science and social studies (Graham & Hebert, 2011).

Classroom

Applications

Facilitate writing to sources sources, enabling students to create text evidence–based answers.

Model for students how to effectively communicate (speaking and listening) when writing collaboratively.

Support students in creating multimodal content that incorporates audio, video, and graphics.

Oral language supports the development of all other literacy skills.

Oral language involves communicating, understanding words or concepts, obtaining new information, and expressing thoughts— skills that are prerequisite to successful reading comprehension, which in turn is essential to successful learning.

Classroom

Applications

Develop higher-order questions that encourage students to think deeply about what the text means rather than simply recalling details.

Foster discussion about complex ideas.

Teach students how to generate questions and answers during and after reading. Students can write their questions or ask other students to respond to their questions orally.

Give students opportunities to observe and practice discussion techniques, clearly outlining what is expected of them.

Active discussions empower language development while also promoting understanding of the text. Student-led discussions get students constructing their own meanings from readings, connecting stories to their personal experiences and prior knowledge, and clarifying their understanding of text events, characters, and vocabulary.

Common Misconceptions

While a popular instructional method, posing open-ended questions to the whole class and calling on individual students both omits many students from the exercise and tends to yield responses that are short and simplistic. The goal is to provide all students with multiple daily opportunities to collaboratively construct meaning from texts—participating in student-led discussions with a partner or in small groups. (Peterson, D., Journal of Early Childhood Literacy).

Integrated Literacies: THEORY INTO ACTION

Reading and Writing Reciprocity

Take advantage of the time-saving and comprehension-boosting benefits of connecting your reading and writing instruction. In their meta-analysis, Writing to Read, Steve Graham and Michael Herbert report that extended writing activities produced greater comprehension gains than simply reading the text, reading and rereading, or reading and discussing it.

Ways to bring reading and writing reciprocity into your instructional practices:

- Have students respond to text evidence–based questions in writing.

- Use core texts as source material for students’ own writing.

- Analyze core texts with a “writer’s eye,” using them as mentor texts for writing instruction and students’ writing.

Source: Benchmark Advance

4. Support for All Learners

Today’s classrooms are diverse in every way—linguistically, culturally, and developmentally, with students of varying academic, cognitive, and social-emotional skill and need.

Yet educators must ensure that all students achieve grade-level expectations while simultaneously meeting each student where they are (Cabell, 2022). And all of this must occur in a supportive and inclusive classroom environment.

This is no easy task. To achieve it, the unique developmental, cultural, and linguistic needs of all learners must be kept at the center of literacy teaching and learning.

The range of developmental needs, especially for students traditionally underserved, is more extensive than ever because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

—U.S. Department of Education, 2021

Classroom

Applications

Engage students with resources that widen their perspectives and understanding of themselves and the world.

Build content-area concept knowledge and essential literacy skills.

Create in-school contexts for students to share their voices and visions through reading, writing, and speaking.

Choose texts that speak to students’ multiple identities, not their reading identities alone.

Scaffold ways for students to share their thoughts and respond to texts.

Academic knowledge and experiential knowledge and cultural knowledge—all of the things that we know, all of the experiences that we have—are all resources for literacy development.

Teachers must attend to the kinds of academic knowledge that they support in school but should also help students to bring their personal knowledge to their own literacy learning—to try to find ways to form those connections as they read, not only for the sake of engagement, but also for their cognitive benefits (Gina Cervetti, 2023).

We should get to know our students…. [and] think of [them] as full of rich, experiential, and cultural resources that they can bring to their own literacy learning.

—Gina Cervetti, Ph.D.,

University of Michigan, Marsal Family School of Education

There is a growing national need for English Language Arts instruction that incorporates English Language Development.

By 2025, 1 in 4 children in U.S. classrooms will be an English Learner. These students come from a variety of backgrounds, speaking upwards of 400+ languages. The majority will be U.S.-born (U.S. Department of Education).

Confronted with the need to learn language and content simultaneously, English Learners may struggle academically.

Students learn language through prolonged exposure that leverages culture and first-language knowledge and includes opportunities to negotiate content and ideas in the target language, with scaffolds and supports that foster learner agency.

Common Misconceptions

Some assume that a gap in oral language background signifies that Multilingual Learners require an oversimplified approach to English Language Arts instruction. However, research shows that Multilingual Learners with developing levels of language proficiency can succeed academically with the right instructional resources—those explicitly designed to engage them in intellectually rich topics while meeting their linguistic needs.

There are multiple benefits to being multilingual, multiliterate, and multicultural in today’s global society.

Dual language mastery benefits memory, mental flexibility, and the ability to concentrate. It boosts creativity, confidence, and the ability to learn in all subjects, leading to higher academic achievement and greater career opportunities.

Knowing more than one language from birth, acquiring a new language through school, or learning languages later in life can provide tangible advantages in many areas. Multilingualism is an asset that can benefit English learners as well as native English speakers in a variety of ways.

—U.S. Department of Education, Office of English Language Acquisition

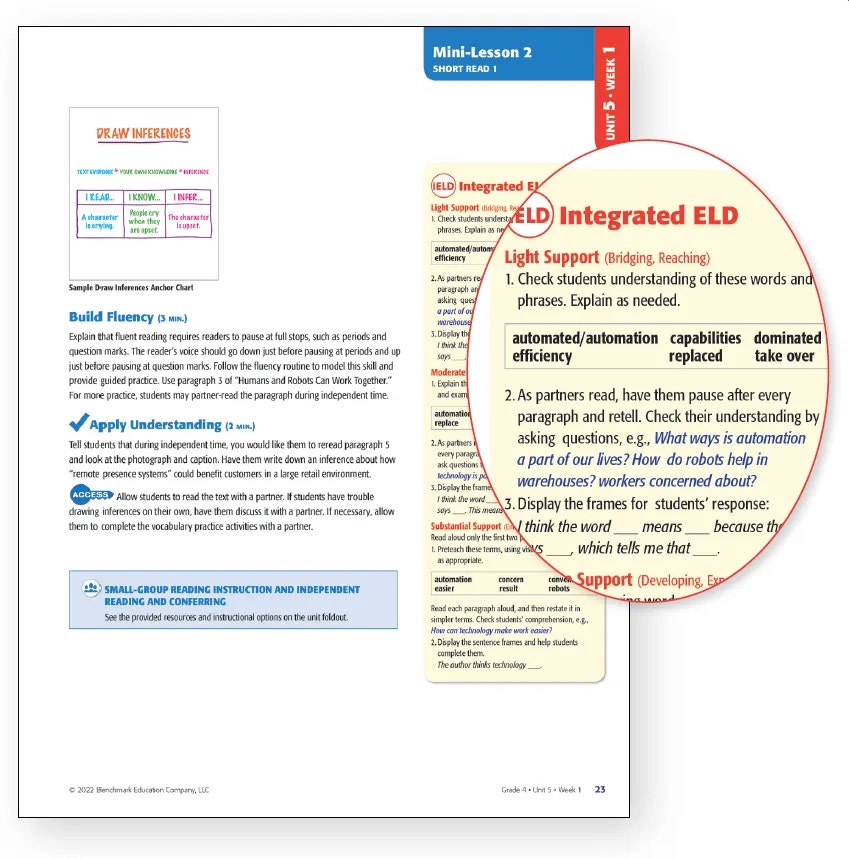

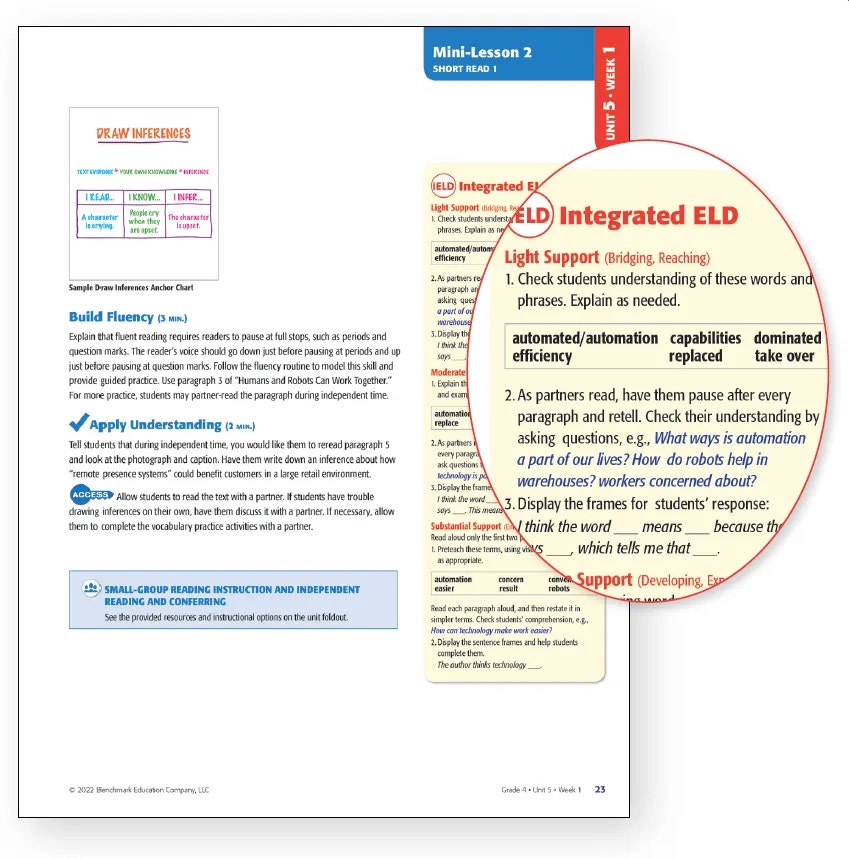

Support for All Learners: THEORY INTO ACTION

Reading and Writing Reciprocity

Supporting all our learners does not need to mean lowering expectations or even the complexity of text. Having the proper scaffolds and layers of instructional support in place can make all the difference.

Ways to support learners while maintaining high expectations:

- Integrate scaffolds for English Learners into core lessons.

- Ensure all students have opportunities to access complex text daily, using additional scaffolds as necessary.

- Look for MTSS resources that align directly to your core instruction.

Source: Benchmark Advance, Grade 4 Teacher’s Resource System

5. Professional Learning & Usability

Professional learning should provide curriculum-based support at every stage of program implementation, promote pedagogical knowledge building, model evidence-based best practices with instructional coaching, and foster collaboration between educators through professional conversation.

When teachers are supported with effective professional learning, everyone benefits.

Skilled teachers have a greater influence on student achievement than any other school variable.

—Opper, 2019; Chetty, Friedman & Rockoff, 2014

High-quality instructional materials (HQIM) align to standards, support rigorous instruction, are grounded in research, reflect diversity and inclusiveness, and are usable.

Usability is not much discussed as an element of high-quality materials, but with the right components in hand, easy to navigate and implement, teachers are more likely to use those resources with fidelity (Wang, Tuma, Doan, Henry, Lawrence, Woo & Kaufman, 2021)—saving time and increasing their effectiveness.

High-quality instructional materials matter too. When paired together, a teacher’s skilled use of effective materials boosts student outcomes.

—Chingos & Whitehurst, 2012

Classroom

Applications

Teacher professional learning will prove effective when it:

- Possesses a cohesive vision

- Cultivates teacher autonomy

- Is ample, sustained, and connected

- Regards teachers’ different learning needs

- Promotes collaboration

—Herrmann & Grossman (2021)

But this pairing does not occur naturally, without support. Instead, evidence points to a critical variable— professional learning.

—Doan, Kaufman, Woo, Prado, Diliberti & Lee, 2002

Professional Learning & Usability: THEORY INTO ACTION

Ongoing Professional Learning

As educators, we form a community of perpetual learners, emphasizing our commitment to continuous learning. Take advantage of opportunities provided at your school or district to further your professional learning. Beyond that, look for ways to sustain your learning throughout the year and align it to your professional goals.

Ways to integrate and sustain your professional learning:

- Study your curriculum. Watch on-demand product trainings and attend trainings.

- Register for webinars led by literacy experts. Look for webinars on topics related to your professional goals or led by authors of your literacy curriculum.

- Listen to podcasts/interviews. Follow literacy experts and keep saved searches related to topics.

Source: 30 Professional Learning videos from literacy experts like Wiley Blevins: research-based phonics routines, implementation videos, and more