- Benchmark Education

- Newmark Learning

- Reycraft Books

- Create an Account

About the Experts

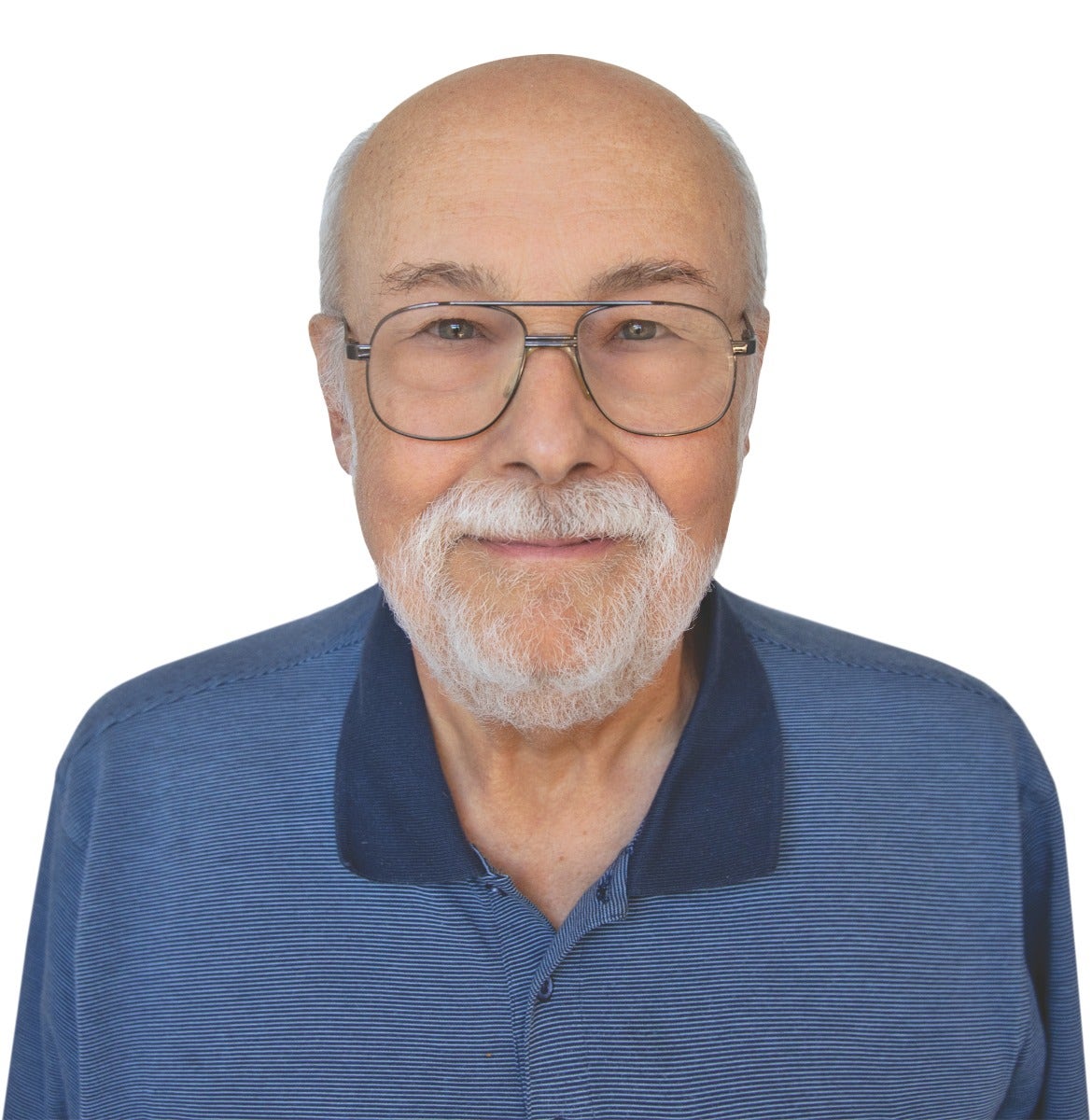

Timothy Rasinski, Ph.D.

Timothy Rasinski, Ph.D., is a professor of literacy education at Kent State University and the author, co-author or editor of over 50 books or curriculum programs. In 2010 he was elected to the International Reading Hall of Fame. In 2020 Timothy received the William S. Gray Citation of Merit by the International Literacy Association, the highest award given by the prestigious organization. Tim earned his doctorate at The Ohio State University.

Lynne Kulich, Ph.D.

Lynne Kulich, Ph.D., is a Senior Director, Solutions Engineer at Renaissance and a former professor, literacy coach, director of curriculum, and a mentor in the Ohio Principal Mentoring Program. She earned a doctorate in Curriculum and Instruction from the University of Akron in 2009 and loved teaching graduate reading courses, as well as elementary students.

Featured Products

Decodable Fluency Builders

Driven by Science of Reading research, Decodable Fluency Builders features a wealth of robust, high-quality texts that provide authentic decoding experiences to help build fluency—the bridge to comprehension.

Spot On

Enrich and expand instruction with small-group resources that build content knowledge.

Reycraft K-5 Hardcover School Library

Connect children to the world around them through books that inform, inspire, and reflect their experiences.

Episode Transcript

Speaker1: This podcast is produced by Benchmark Education.

Kevin Carlson: Reading fluency. It's the ability to read with speed, accuracy, and appropriate expression. It's the bridge between decoding and comprehension. And few people, if any, would claim to be more expert on it than Dr. Timothy Rasinski. He and Dr. Lynne Kulich join us for this episode. Throughout this season, educator and author Patty McGee talks with leading literacy experts like Tim and Lynne to explore current understandings and nuances of teaching and learning literacy. Our aim is to present a 360-degree view of literacy that positions us to address the needs of all students in today's classrooms. I'm Kevin Carlson and this is Teachers Talk Shop.

Dr. Timothy Rasinski: We want kids to be able to decode words, but really what we want them to get to is the point of decoding words automatically or effortlessly. When you give minimal effort to your decoding, you can give maximum effort to your comprehension.

Kevin Carlson: That is Dr. Timothy Rasinski. Tim is a Professor of Literacy Education at Kent State University and former director of its award-winning reading clinic. He is a prolific author, has been elected to the International Reading Hall of Fame, and in 2020 was awarded the William S. Gray Citation of Merit by the International Literacy Association. That is the highest award given by the largest and most prestigious organization devoted to literacy development in the world. The National Reading Panel included his research in a body of scientific evidence to support reading fluency. That research was a study about the Fluency Development Lesson.

Dr. Lynne Kulich: Educators often ask, “Don't they get bored reading that same passage five days in a row?” Nope. They definitely do not. You change up the purpose, you change the audience, you embed that creativity. Oh, my goodness, we had so much fun with it.

Kevin Carlson: That is Dr. Lynne Kulich. She is the director of early learning at NWEA. She has also worked as a professor, literacy coach, director of curriculum, and a mentor in the Ohio Principal Mentoring Program. She and Dr. Rasinski are longtime colleagues and have presented together about reading fluency. Patti McGee spoke with Doctors Rasinski and Kulich recently about the benefits of fluency mastery and about the fluency development lesson. But she started with the basics.

Patty McGee: Can we just talk about what fluency is and why it's important?

Dr. Timothy Rasinski: Lynne, do you want to take a first crack at that one?

Dr. Lynne Kulich: Sure. Absolutely.

Dr. Timothy Rasinski: Put you on the spot.

Dr. Lynne Kulich: Yeah. Yeah, happy to. You know, I think the best way to come at that is, talk about what it really isn't. And I think there's some miscommunication still that fluency is just about reading rate. Sometimes we refer to that as words correct per minute. And you know, Tim and I, we live and breathe in this space and we know that there are three domains or buckets to it. It certainly is rate. That's a piece of it, though. So you've got rate, you've got accuracy, and prosody, or that intonation—that expressive reading. But prosody is kind of interesting in that it's also an outcome of comprehension, because when students are in that space reading and they're comprehending in real time, they fully understand which words to emphasize, or they understand what that exclamation point means or that complex syntax, and they really kind of change up their intonation to match their understanding of what they're reading. So it's kind of an interesting component.

Dr. Timothy Rasinski: We often use that term, “rate of reading,” and we do so appropriately. But I just want to mention that rate reflects the underlying concept of automaticity and word recognition. We want kids to be able to decode words, but really what we want them to get to is the point of decoding words automatically or effortlessly, just like most adult good readers are. And the reason for that is because when you give minimal effort to your decoding, you can give maximum effort to your comprehension. John Pikulski and his colleague David Chard years ago called fluency the bridge between word recognition on one end and comprehension at the other. And most kids, of course, they develop that bridge on their own just through lots and lots of practice, but a significant number of kids don't. And that's why fluency needs to be something that is an integral part of our literacy curriculum through the primary grades and even well beyond that, for sure.

Patty McGee: So glad you brought that up, because that brings me to a question that's probably at the forefront of everyone's mind right now before we go deep into supporting fluency within the classroom. There's so much out there right now talking about phonics, the Science of Reading, and it is obviously an important conversation to be having. And also, I'm curious where fluency fits into all of this.

Dr. Timothy Rasinski: This focus on phonics is appropriate. But it's not the whole ballgame. And what I see happening is it's taking up so much of the oxygen in the discussion that there's no time left to be able to talk about some of these other elements, like comprehension, building vocabulary and, in our case, building reading fluency with our students. Phonics will take you so far, but then you have to cross that bridge and that's where fluency kicks in.

Dr. Lynne Kulich: Yeah. I would concur and say that in my current work, when I'm really all over the country and even internationally talking with educators, yes, phonics is important. But my concern, and I know it's Tim's, is that message, especially this notion of the Science of Reading, evidence-based research on how kids learn to read, it gets muddled down. And the only message that people kind of hang their hat on is explicit, systematic phonics instruction. Absolutely, but let's not forget about explicit, systematic phonological awareness, fluency, vocabulary, comprehension, content knowledge, all of those things. And you know, the Science of Reading is not new. It suddenly has become a newer notion, but it's been around for decades now. And the National Reading Panel in 2000 said, “Hey, there are these big five ideas or constructs and they all need to be explicitly taught.” And if we only focus, like Tim said, on phonics, then we're going to see these reading gaps that they're never going to close, and we're right back to square one.

Dr. Timothy Rasinski: Exactly. There's a strong scientific basis for the teaching of fluency. And interestingly enough, it's not just fluency. When you focus on fluency, we find kids becoming more automatic and more prosodic or expressive. But we also find that their word recognition improves, their phonics improves, their comprehension improves. So, it's something that really is overarching. It's something that can really make a difference.

Our colleague Tim Shanahan, who is a well-known scholar and subscribes to the Science of Reading, says that equal amounts of time should be devoted to both phonics and fluency every single day. And when he was director of reading for the Chicago schools, he mandated that, and he got some exceptional results. And his mandate, by the way, was not just for the primary grades, it was all through every grade level. Of course, in an urban school district like Chicago, you find many, many students struggle in the area of reading. So, he got remarkable results by making sure that fluency was an equal part of that curriculum.

Patty McGee: A couple decades ago, we bought this house that we live in, and I really wanted my gardens to turn out really beautiful. So, my mom gave me some of her flowers from her gardens and I overdid it on the black-eyed Suzies. They looked beautiful, but it really wasn't a garden that was creating benefits for other plants and other possibilities to come together in what we know would be a full and beautiful garden. And I think about what we're talking about in a similar way—yes, the systematic phonics instruction is a necessity and is beautiful in its own right. And when we have a garden full just of that, the garden itself is really missing some other beautiful parts that are important to make it whole.

Dr. Timothy Rasinski: Yeah, I love that, what you just said. To me, it gets back to that notion of, when you create a garden, of course you have to focus on science, get the right mix of plants and fertilizers and all that. But that sense of beauty, that artfulness—and that's where Lynne and I like to think of our efforts in instruction. Yes, we want to follow the science, but we also want to follow the artfulness of teaching. Teachers get into teaching because they're creative. They're not there just to follow some curriculum script that's out there. So thanks for bringing that in, this notion of artfulness.

Kevin Carlson: After the break, the science and the art of fluency instruction. Stay with us.

Announcer: Application and practice. These are the cornerstones of a new foundational literacy series from Benchmark Education: Decodable Fluency Builders. Your students will be immersed in a collection of carefully crafted fiction and nonfiction texts that combine phonics, high frequency words, and language comprehension work. You'll see your young readers accelerate from mastery to transfer in reading, writing, listening, and speaking. Two-sided Teacher Cards accompany each text to help you plan lessons, and you'll have on-demand Professional development available 24/7 at Benchmark Academy. Guide your young readers towards comprehension with Decodable Fluency Builders. Learn more at Benchmark Education dot com.

Patty McGee: I'm so curious about your own backstory that brought you into this passion of fluency.

Dr. Timothy Rasinski: Back in the mid-to-late 70s, I taught school, first as an elementary school teacher and then then I got in as an interventionist, working with kids who struggle. And I still remember quite distinctly working with kids who were struggling reading. And I did everything I was supposed to: Work on phonics, work on vocabulary, work on comprehension. And for the most part, the students I was working with were making progress. But there was a significant number who weren't. I like to say they were flatlining in terms of their literacy development. Fortunately for me, I was doing my Master's in reading at the time, and the profs had us reading some of these articles that were just beginning to appear on reading fluency: “The Method of Repeated Readings,” by Jay Samuels. Another one was by Carol Chomsky: “After Decoding, Then What?” After you teach kids phonics and they're still not making progress, then what do you do? And her answer was, “Fluency.” So I read those and I said, “Oh, my gosh! I had never thought about this before!” So I began to apply some of these methods—repeated readings, having kids read something and hear it read to them at the same time. And all of a sudden, these kids began to take off. And in some cases, it was spectacular, the growth they were making. In other cases, it was more muted, but it was always there. So when I decided to go on for my doctorate, that was going to be the focus of my dissertation research, which continued and to discover the scientific basis for reading fluency.

Dr. Lynne Kulich: Fortunately for me, Tim is older, so I don't know if he knew at the time he had a fan club, but he definitely did. I was probably that number-one fan. Flashback to gosh, mid-90s, I was working for the Georgia Department of Education. I taught French, I was part of their FLES program. So, when I was teaching first and third graders French, I was also working on my Master's degree. So certainly, implementing some of those best practices often that we talk about as assisted reading practices—so explicitly teaching fluency while I was teaching French. But I was also working on my master's degree in Elementary Ed, and I'd stumbled upon a lot of Tim's work, including something I know we'll talk about eventually, the fluency development lesson. Well, my family, we moved back to Ohio and I got a job as just a regular first grade classroom teacher here in Canton, Ohio, where I live. And I started implementing a lot of these best practices that I was reading about from Tim. I kept reading—Richard Allington talking about, fluency was that forgotten, neglected domain, almost like the Island of Misfit Toys.

Fluency instruction for me allowed me to experience such joy teaching my first, second and third graders. And that's where that artful piece comes in. It allows you to build relationships. It's not about specifically putting students on a computer or doing a workbook page, right? It's actual human interaction, working on these assisted reading practices that really feeds that soul. We'll talk later about fluency development lesson, but I decided to do my doctoral research on it, and that's when Tim kind of heard and said, “Hey, you know, I'd like to participate in this. Can I be on your doctoral committee?” And, when Tim knocks, you open the door.

Patty McGee: You brought up that aesthetic approach, that human part of teaching that's so essential. And Tim had referred to thinking about fluency instruction as artful, as well as scientific. Could you just talk a little bit more about this, how we can bring together these thoughts around the art and science of fluency instruction?

Dr. Timothy Rasinski: One of the basic tools for teaching fluency is repeated reading, where you ask students to read something multiple times. What the research says is that when kids do that, of course they improve on that piece they practice. But then there's a carryover to things they've never seen before. So, there's this generalization. But how do you get kids to engage in repeated readings? “Read this text four times, tell me when you're done”? You'll get kids rolling their eyes at you. It just dawned on me somehow that repeated readings is just another name for rehearsal. If you're going to perform something for an audience, you have to rehearse it. And of course, that's in actual repeated readings. Not for reading fast, but for reading with expression.

Well, the next question was, are there certain kinds of texts that are meant to be performed? And of course, poetry is the top of our list. But there's other things like songs and reader's theater scripts and speeches from American history, from world history, for that matter. These are texts that are meant to be performed. And because they're meant to be performed, they have to be rehearsed. So, it's just a natural. And of course, think about it, poetry, songs, scripts, you know, those are very artful texts that often get neglected in our classrooms.

Dr. Lynne Kulich: Tim brought up this notion of repeated reading not for the sake of increasing rate necessarily, right? Jan Hasbrouck talks about how there is a lack of evidence that suggests that any student with a reading rate beyond that 50th to 75th percentile on a grade level text doesn't in turn benefit their comprehension. In other words, increasing their speed above and beyond that might actually hinder comprehension. So that whole goal of repeated reading is not just to get them to read faster. Instead, that repeated reading activity, really, it just becomes a joyful experience. And it's not about reading it faster. What's the point? There's nothing joyful in that.

Dr. Timothy Rasinski: I recall a few years ago in our reading clinic, we had two second graders show up. They were experiencing difficulty in reading. And of course, one of the things we do is we ask the kids to read some passages for us. And I still remember both of these second graders looked up at the clinician, the teacher who was working with them and said, “Do you want me to read this as fast as I can?” And I think, where's that coming from, all this emphasis on speed? We want kids to become fast, but we want them to become fast the way all of us became fast readers. And how was that? We just read a lot. We became automatic in our word recognition and our speed just naturally increased as a result of that.

Can I tell you a little study I did a few years ago with another colleague? It was kind of a silly study. We were thinking about, what are some examples of the most fluent reading we can think of? And we thought, “Well, how about speeches?” Maybe Dr. King's “I Have a Dream” speech and the speech by John F Kennedy where he says, “Ask not what your country can do for you.” You know, that famous phrase. So what we did was we found the recording of both of those speeches and then we subjected it to an oral reading fluency test, counting the number of words correct per minute. And what we found was that their words correct per minute score would have put them in a remedial reading class. They read slowly and they read and did it purposely. They could have read it fast, but it would not have that same inspirational, artistic meaning if they had read it as fast as they could. They read it to make emphasis and make meaning that would last the ages.

Dr. Lynne Kulich: I share that all the time, because I think it really kind of flies in the face of this notion—you know, when kids look at us and they do, “How fast do I have to read?”

Dr. Timothy Rasinski: Yeah, yeah.

Dr. Lynne Kulich: And that study—everyone I mean, everyone—if you are an American native, you know the JFK speech, you know the Martin Luther King Jr. speech, and you would not want to listen to it at a high rate.

Dr. Timothy Rasinski: Right. Right.

Patty McGee: One of the questions that's popping into my mind is, then, to what extent do children who study with reading experience difficulties in fluency?

Dr. Lynne Kulich: Correct me if I've got my statistics wrong, Tim, but I believe if we look at fourth grade proficiency scores reading, across the nation, I think it's something like 75 to 90% of those students who are not proficient. So having difficulty comprehending, that's the purpose of the assessment. If we unpack that, or peel back the onion, what we see is, their difficulties lie in that area of phonics, word recognition, and fluency. So, if we can explicitly and systematically close those gaps by some of these evidence-based fluency practices, and certainly once—fluency instruction, as Tim mentioned, is that bridge. We're not suggesting with preschool students who haven't yet recognized letters and phonemes that orthographic mapping needs to occur. But as they begin to do that and they start to decode those words and phrases, that's when that bridge arrives, right? But if we look at fourth grade proficiency statistics, we can see that the gaps are right there. We know where they're at.

Dr. Timothy Rasinski: Another study that came up just a few years ago, it was done by the National Assessment of Educational Progress, U.S. Department of Education. And again, they looked at fourth graders and different measures of fluency. They looked at decoding, they looked at automaticity, and they looked at prosody. And what they found was that those two elements associated with fluency—prosody and automaticity—seemed to have a greater impact. Kids who struggled—that was the areas where they had the greatest level of difficulty. Their word recognition actually was not all that bad when compared with where they needed to be. But when you looked at those other two areas, those were significantly below where they needed to be. So again, we're seeing the research from a number of different angles that says, yes, phonics is important, but it only gets you so far. And unless we address the fluency issue, we're not going to have kids crossing that bridge to proficient reading. And we're going to be right back where we started.

Kevin Carlson: After the break, some basic tools for teaching fluency. Stay with us.

Announcer: Reflection is the catalyst that sparks all students toward a truer understanding of the reading process. In Reflective Readers: The Power of ReadersNotebooks, author and educator Travis Crowder helps teachers nurture their students’ engagement.

Travis Crowder: I'm Travis Crowder, a seventh grade English language arts teacher. I've been a teacher for 14 years and Reflective Readers is my second book. I was prompted to write this book because I wanted to return to this emotional connection to reading. What is it about a book that inspires us to connect, that causes us to see ourselves and to just get lost in the pages of story?

Announcer: Find out more about this and other titles at PD Essentials dot com. Go teach brilliantly.

Patty McGee: You both made such a strong case for fluency—what it is, why it's important, and the many facets of fluency and how they impact reading. Now let's shift our conversation to the classroom space itself. What are some basic tools for teaching fluency?

Dr. Timothy Rasinski: I like to identify five. First is we need to model fluent reading for our kids. A lot of children, when you say “fluency,” they don't know what you're talking about. So why not read to children fluently and then talk about it? “Did you notice how I changed my voice when I became a different character?” “What were you thinking when I had this long, dramatic pause in my reading?” And get kids to notice that you're using your voice not only to assist their comprehension, but also to improve their satisfaction with the reading. So that's one.

Two would be assisted reading, and there's various forms, and then I'll let you talk about that. But that basically is when you read something and you hear it read to you at the same time, and that can be a variety of forms. The one I often talk about is choral reading, when you read together.

Then we have wide reading. Of course, we all know what that is. Read a lot! One thing after another. Read a story, talk about it, and you move on to the next one.

But also there’s repeated reading, where you have kids read something multiple times and then move on to the next piece.

And then the fifth piece is phrasing. The idea, if you think about somebody who's a not-so-fluent reader, these are children—and adults, for that matter—who read in that word by word, staccato-like manner. And what we do know is that good readers read in chunks, meaningful chunks. I've heard it said that the word is not the natural unit of reading, it's the phrase—the noun phrase, the verb phrase, the prepositional phrase. And yet, when you have children read words like “the” or “uh,” as if they're meaningful units, they're not going to go very far before they're rolling their eyes and saying, “I don't know what this is all about.” So, focusing on that chunk, as well. So, to me, those are those five basics and it's how you put it together, I think that really matters.

Dr. Lynne Kulich: When Tim talks about assisted reading, there's choral reading, everyone reading obviously together—usually can be led by that proficient reader, that teacher, right? There's, you know, obviously echo reading—I read a line, you read a line, that type of thing.

Something that comes to mind, just kind of a little story about phrase reading that Tim brought up and this notion of choral reading—I had one year teaching first grade, I had 27 first graders. Loved those students. We had a blast. But what I did is, I wanted to work on building their fluency explicitly, and I wanted the phrases that we were reading, chorally and periodically, throughout the week—I wanted them to be meaningful, not just phrases I pulled from anywhere. So, what I did is, I took all 27 of my students and I created a short little sentence, to Tim's point about your noun verb, your phrase, a short sentence about each student, and I wrote them out. So, we had 27 sentences, and each sentence or short phrase was about that student, and everybody knew, pretty much, why I chose the phrase I did. And periodically we'd take a brain break and we'd say, “Okay, let's read our sentences chorally.” And I remember having sentences—I had a little boy named Joey Ball, and he just was the happiest kid, and I had a sentence with exclamation points that said, “Having a ball with Joey Ball,” because we always used to say that, or, “Tori broke her arm on the playground.” So, I had a sentence that said, “Oh, no, Tori broke her arm,” and you've got question marks and exclamation points or commas and all of those things in there. So, the phrases were meaningful. So we read them quarterly, we read them repeatedly, and I changed them up throughout the year, and we just had so much fun with them.

Dr. Timothy Rasinski: Again, there's that notion of artfulness. When you took your students, you could have just said, “Let's turn to page 28 of our textbook and read that,” but you personalized it and made it engaging and authentic and—what's the other word—aesthetic for the kids. It's something that made them feel good. And it came out of your creativity as a teacher. That's what we want in our teachers. We want them to have that agency to use the science, but in artful ways.

Patty McGee: I'd love to dig into any other ideas you might have in those five categories, I guess, of modeling fluent reading and talking about it, of assisted reading, of wide reading, repeated reading or phrasing that have that kind of playful tone.

Dr. Timothy Rasinski: Well, I sometimes talk about the use of reader’s theater over the course of a week, where children work on small, short texts that you can find pretty much everywhere. But can you imagine where, earlier in the week, the teacher says, “On Friday we're going to have a reader's theater festival and invite all the other classes to come to our class, and moms and dads”? On Mondays, the teacher assigns two or three children to each group, there might be five or six scripts that they’re going to be performing. Monday, she reads them all, puts them under a document camera, and models them for the kids while they follow along. Tuesday, they read them all chorally as a group. On Wednesday, the teacher says, “Okay, break up into your small groups, practice on your own, and I'm going to go around coaching, giving feedback, helping out, telling you what a great job you're doing. Thursday, we'll have a dress rehearsal, and then on Friday, we'll invite the other classroom in and dim the lights and mom and dad and the school principal will come. We'll perform for the class! And then the next week we'll make this just a regular routine.”

So, you have the modeling, the assisted reading, the repeated reading, all those elements. I didn't mention the phrasing, but the teacher could easily embed in the conversation early in the week, noticing how, when she read or he read, they were grouping the words together into meaningful phrases.

That’s one approach that I know my friend Cameron Carter, a first-grade teacher in Columbus, Ohio has done. And I just love seeing that. I just love seeing the faces of children when they're given that opportunity to be the star. That's what we want kids to be.

Patty McGee: Oh, this is so exciting to think about the possibilities. Now we're going to start to go toward the end of our conversation here. But I definitely want to link this into what you both advocate for, the fluency development lesson. Why should teachers do this? What is it, and how can they use this with their students?

Dr. Lynne Kulich: While I was working on my master's degree in Elementary Ed, this is when I stumbled on Tim and his colleagues, their work with the fluency development lesson. And I thought, “Wow, this isn't something I need to purchase. It's an evidence-based instructional practice that really encompasses all of those important ideas in terms of fluency instruction—assisted reading, reader’s theater, etcetera.” I was teaching first grade at the time, and then inevitably moved to second and third, and still implemented the fluency development lesson. Essentially, I took his lesson, really with his blessing—and anyone is welcome to do this—and adapted it a little bit. I followed his procedures using a text, and while Tim has mentioned you can use any text when you're practicing fluency, we love poetry, so I use poetry with my students. But my students had a new poem each week. So, Monday morning they got the new poem and I just started implementing those fluency practices—choral reading, echo reading, partner reading. But then we took it a little bit further. We didn't just read it, we started peeling it back a little bit, like, “Wow, okay. In my scope and sequence for this week in first grade, we're talking about r-controlled vowels. Oh, my goodness, let's see if we can find those r-controlled vowels in this poem.” Or we're talking and reading about a particular theme, focusing on content knowledge, so I'm selecting a poem that enhances that theme that we're talking about.

So, each day, we would read that poem, but the support I provided was very much scaffolded. First day, I didn't expect students to read it on their own—a lot of just choral reading, maybe a little repeated reading. But each day of the week, I sort of stepped back and let the students start reading it more on their own. But I also gave them a different purpose for reading every day. Educators often ask, “Don't they get bored reading that same passage five days in a row?” Nope. They definitely do not. You change up the purpose, you change up the audience, you embed that creativity. Oh, my goodness, we had so much fun with it.

I incorporated things like mystery readers, and we acted like we were actors and we changed up our intonation to pretend we were sleepy when we read it. And this was all by, like, Day Four or Five, because now they were comfortable decoding it. But the biggest piece is, I incorporated that school-home connection. My kids had a poetry folder, so every Thursday, they took that poem home. By then, those students were very comfortable reading that poem to someone at home, and then that family member would sign the lucky listener sheet. But then, also, we know that reading and writing are synergistic. So, on the back of that poem was a writing activity. And again, educators will say, “Really? The first week of first grade?” And my response is, “Really.” Because they can draw a picture and write some sort of a caption. Doesn’t matter if it's spelled incorrectly, right? They're writing and that's where they're at.

As the year progresses, they have all of their poems in this folder with all of their written responses on the back and you can see this learning progression. They bring that poetry folder back on Friday, and I just don't check it off. Yes, they turned it in, homework has been satisfied. I would read their written responses and I'd make comments. So now it was this written dialogue back and forth. And then periodically, like at that semesterm, we'd have a poetry party and I invited the families in, other educators, administrators, and we'd celebrate their reading accomplishments and they would read some of their favorite poems. But I really followed his script of this fluency development lesson, just kind of amended it a bit, to use that same text all throughout the week. And then imagine, you know, all students are taking a test and some have finished before others. What should students do? Well, they have that poetry folder now in their desk. I would instruct them, “Hey, open up your poetry folder and go back through and silently read some of those poems, especially the ones you really liked.” It's that joyful, artful experience. We go back and reread things we love.

That was really the first time I started implementing his fluency development lesson. And then I took it to a different level with my doctoral research.

Dr. Timothy Rasinski: Your dissertation was on with English Language Learners, and you would think, “Well, these are the kids who first need work in phonics,” and yet the progress you saw your children making, by using this fluency lesson on a regular basis, was really quite spectacular and reinforced all the research that had preceded it. We use it, have used it, in our reading clinic, as what we call our core lesson. Whether or not they're first graders or eighth graders, we find that these foundational skills are usually the area of problem for them. So, this lesson is one that we do on a regular basis, well, a daily basis, with the kids. And again, in five or six weeks of instruction, we find kids making exceptional progress. Whether or not you're talking about a clinic, a classroom, summer school reading, it's something that across the board seems to have an impact on children. What I love about it is the simplicity of it. Once you get the model in your head, it's just a matter of basically changing the text the kids are reading on a regular basis, but they go through the same process: Learn to master a text by engaging in those tools that we talked about earlier—modeling, assisted reading, repeated reading, focus on phrasing, and then eventually performing for that audience in that poetry party they might have.

Patty McGee: It's a pure pleasure listening to you and the possibilities of what we can do around fluency. It seems endless. It seems playful. It seems like one of the healthiest vegetables that's out there for reading, learning, and that kids just find so much joy. And you even brought up that social emotional learning aspect that's embedded into it all. It's just like a win-win all around. All that you've shared with us have both inspired me, and, I'm sure, listeners, to really deepen our understanding and elevate the importance of fluency instruction, while also thinking about how naturally it can be part of every classroom. So Lynne and Tim, thank you so much for joining us today. We are certainly going to be flying with all this information.

Dr. Timothy Rasinski: Thanks, Patty We're glad to be part of your podcast and we'd be happy to come back at another time to go a little bit deeper into all of this. But thanks again for that opportunity.

Dr. Lynne Kulich: Yeah, definitely. It's just it's been a great time. Love to talk about fluency with Tim.

Kevin Carlson: Thank you, Dr. Tim Rasinski and Dr. Lynne Kulich. Thank you, Patty McGee. And thank you for listening to Teachers Talk Shop. Tim and Lynne have a new book coming out soon that I want to tell you about: Fluency Development Lessons: Closing the Reading Gap. It features fluency development lesson plans created for poems that were written specially for the book by David Harrison, and it discusses the research and instructional techniques that are embedded in those lessons. The book is designed with usability in mind. Each poem has five days of lessons that meet ELA and content area standards, and it helps you learn to develop your own fluency development lessons.

So again, the name of the book is Fluency Development Lessons: Closing the Reading Gap. It's by Dr. Timothy Rasinski, Dr. Lynne Kulich, and the poet David Harrison, coming soon from Benchmark Education's PD Essentials line of professional development books. PD Essentials dot com.

To learn more about our guests, listen to previous episodes, find transcripts, and explore related resources, please be sure to visit Teachers Talk Shop dot com. Thanks. For Benchmark Education, I'm Kevin Carlson.