- Benchmark Education

- Newmark Learning

- Reycraft Books

- Create an Account

About the Experts

Nathaniel Hansford

Nathaniel Hansford is a teacher of 11 years. He is the author of The Scientific Principles of Teaching and The Scientific Principles of Reading Instruction. He has taught Grades K-12; currently he teaches intermediate. Nate is the lead writer and content creator for Pedagogy Non Grata.

Featured Products

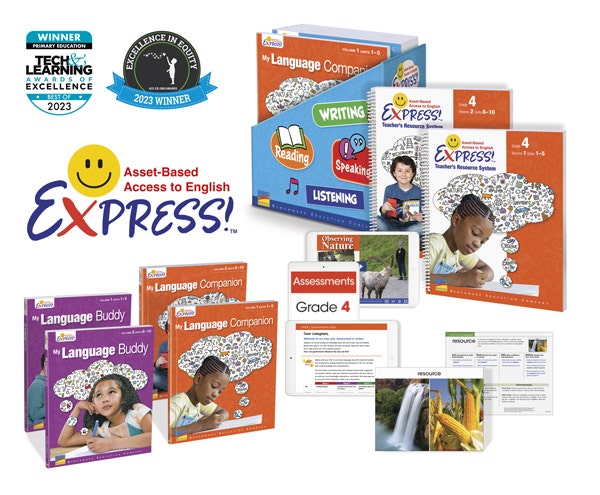

Express!

Asset-Based Access to English

Introducing a new K-6 English Language Development program to promote language learning.

Learn MorePut research into practice with high-quality instructional materials designed for English Learners at any level of language proficiency. Discover programs that engage minds, elevate achievement, and empower every learner. Visit Benchmark Education to get started today.

Episode Transcript

Announcer: This podcast is produced by Benchmark Education.

Kevin Carlson: Meta-analysis. This statistical technique combines data from multiple studies about a common research question to draw a single conclusion.

In this episode: “English Learners and the Science of Reading: What We Know from Meta-Analysis.”

I'm Kevin Carlson, and this is Teachers Talk Shop.

Nate Hansford: We always have to consider the needs of the student. Meta-analysis is a great tool for looking at “What does the average student best benefit from?” But whenever you have a student coming to you who's coming from a specific context, you have to look at their context.

Kevin Carlson: That is Nathaniel Hansford—Nate. He is a teacher of 11 years, the author of The Scientific Principles of Teaching and The Scientific Principles of Reading Instruction. He has taught Grades K to 12 and currently teaches intermediate grades.

Nate is the lead writer and content creator for Pedagogy Non Grata dot com [www.pedagogynongrata.com], which bills itself as “your go-to source for evidence-based education” and offers articles, books, a podcast, and other resources.

Benchmark Education's Dr. Jennifer Nigh sat down with Nate recently to discuss English Learners and what we know from meta-analysis research and the Science of Reading.

Dr. Jennifer Nigh: So, Nate, thank you so much for joining us today. I know that you are coming off of a very busy school day, so we're thrilled that you are sitting down with us to have this conversation today. So welcome.

Nate Hansford: Thank you. It's nice to be on the podcast with you.

Dr. Jennifer Nigh: Great, thank you. Well, let's go ahead and get started. Why don't you tell us a little bit about yourself?

Nate Hansford: Yeah, I'm a teacher of 12 years now. I am a specialist in reading and special education—not that I think those qualifications matter too much. I am the author of a couple of books on education—now I have a new one coming out right around this time, although I guess by the time this is aired, it'll be long out, called The Scientific Principles of Teaching . It's really a second edition of that book. And I also have another book published, The Scientific Principles of Reading Instruction.

I'm really focused on this idea of, how do we use meta-analysis to learn what is the most evidence based strategies in teaching? I've worked in some pretty tough settings, and I'm a firm believer that as teachers, we should have access to the teaching strategies that are going to give us the biggest bang for our buck, for lack of a better word. And I think meta-analysis is the best tool to discover what those are. So it's sort of become a little bit a hobby, a little bit of obsession, trying to find out what are the best teaching methods and using meta analysis to do that. And I've also co-founded a website dedicated to that topic called Pedagogy Non Grata.

Dr. Jennifer Nigh: Great, great. Well, I know we're going to talk a lot today about English Language Learners and evidence-based practices. Because meta-analysis plays such an important role in helping us to just understand what are evidence-based practices, tell me a little bit about that. Why meta-analysis, before we start talking more about English Language Learners and the evidence based practices that support them?

Nate Hansford: Yeah. You know, I think they do this poll every year that shows people's faith levels in science. And the polls have actually shown over the last several years that people's faith in science is going down. And I think part of the problem is how the media reports on science. We hear, “What does the newest study show?” rather than, “What do all the studies show?” And I love to look at eggs for this, because everybody has heard someone say something to the effect of, “One day they say eggs are good, the next day they say eggs are bad—how the heck do we know who to believe? I don't think science knows what they're talking about.” And this is a byproduct of the fact that sometimes scientific studies have variability due to the designs, the populations, the samples. And the results can be different study to study. So meta-analysis tries to normalize this by looking at what is the average impact across multiple studies or hopefully all high-quality studies on that topic. And I think this is a much better way of looking at it because sometimes you have outliers. You can have studies where you have negative outcomes and studies where you have extremely positive outcomes. It makes way more sense to take an average of all of these studies, in my opinion, than to try and find either the best study or to just pick one study where you like the outcome.

Dr. Jennifer Nigh: Yeah, that makes a lot of sense, because there's also contextual factors and there's that argument about generalization. So if we're talking about English Language Learners today or Multilingual Learners—there's a lot of terms that are obviously thrown around to describe these students—tell me a little bit about your experience with those students. What do you mean when you're using the term “English Learners” or “Multilingual Learners,” and in what context did you work with those students?

Nate Hansford: Well, my very first year as an officially licensed teacher, I went and worked in South Korea, teaching Grades 2 to 6, as an English teacher. And then two years after that, I moved to the far north of Canada working with indigenous students. And that's a very different context, because a lot of those students, they learn English in their homes, but most of those parents, they're learning some combination of Cree and English growing up and there's a lot of Cree words thrown in. And there are also historical contexts, like residential schools that have lowered some of the academic success rates in those communities. So it's often referred to as an ELL instruction. And I've also worked teaching in summer literacy camps, specifically for ELL students.

Dr. Jennifer Nigh: Okay, great, great. And it sounds like the main goal of that was to become proficient in the English language, whether we're talking about speaking and listening, or whether we're talking about reading and writing or all those things combined. Is that about what you were focused on?

Nate Hansford: Yeah, that was definitely always my job.

Dr. Jennifer Nigh: Great, great. All right. So then let's unpack that a little bit. We know the context that these students can be in. We know what the goal is, which is, of course, to make sure that they have proficiency in both language and literacy. But we've also got this conversation going on right now about the Science of Reading, which is absolutely fabulous because it is raising to the surface some of the things that we really need to pay attention to. But within that body of research, a lot of it is primarily focused on students in that K-3 space and students who are native English speakers. That's not to say that—we both know that there is a lot of research for English Learners also—but here in the States especially, we have almost 5 million students who are labeled or considered English Learners. So let's contextualize that with the Science of Reading. What does the Science of Reading say for those students as they're learning English and that being the goal—literacy and language? What do we know from the Science of Reading?

Nate Hansford: Yeah. Well, I think first off, before we even talk about what is the science for ESL learners or ELL learners, I think we need to realize that some of the science that is for primary learners is going to connect and carry over. It’s not like learning happens in a vacuum. It’s the same thing when you have, in my opinion, a struggling reader in Grade 7 who's either had lack of schooling or they're dyslexic, they have needs, in some cases more similar to that of a student in Grade 2 or Grade 3, rather than a student in Grade 8, because that's where they're coming in. You look at Dr. Linnea Ehri’s Stages of Reading Development and we have specific phases in which students acquire language. So if you have students who are still in that early language stage where they don't even have proper pronunciation of all their words, that the type of reading instruction that we're going to see in a primary class for native English speakers is going to be more similar than the type of English instruction that we would see in, say, a Grade 7-8 ELA class, at least ideally, in my opinion.

You mentioned how we might not have as much research, and the research is definitely focused on helping kids learn to read K to 3 for native English speakers. However, there's about by my count, there's at least 15 meta-analyses on the topic of teaching students how to read who are learning English as a second language. And most of the outcomes seem very similar to me to what we have seen in that K to 3 range and what we typically refer to as the Science of Reading, because, well, Science of Reading is a body of research and does not specifically apply to approach. People have often interpreted that to mean a type of instruction, although that's obviously a little bit of a misinterpretation.

Dr. Jennifer Nigh: Yeah, yeah. So one of the things that I was thinking about when you were talking about, you may have a seventh grade student, let's say, that's coming in, that is an English Learner. And that student might need, based on what you have found across these different studies, a lot of the same things that a native English speaker needs in the early grades as they're acquiring literacy. Am I saying that correctly?

Nate Hansford: Yeah, absolutely.

Dr. Jennifer Nigh: Good.

Nate Hansford: I think something we should be thinking about too is just, we always have to consider the needs of the student. Meta-analysis is a great tool for looking at what does the average student best benefit from. But whenever you have a student coming to you who's coming from a specific context, you have to look at their context, and I would say if you have any struggling reader, whether they’re Grade 7, Grade 8, Grade 2, learning English as a second language or a fourth language, you have to still look at those specific needs. And I think the first step is always going to be assessment.

We know that most struggling readers benefit from phonics, but you might get a struggling reader who is proficient in their phonics knowledge and doesn't need additional phonics language instruction and needs other types of instruction. So I believe strongly that the first step when you're trying to support students who are behind where we want them to be, for whatever the reason be, the first step is always got to be assessment so we can diagnose how best to help them.

Kevin Carlson: After the break: Motivating older students. Stay with us.

Mid-roll announcer: Do you need a comprehensive ELD program to help your multilingual students acquire key skills they need to succeed? Then you need to learn about Express! from Benchmark Education Company. This new print and digital program for Grades K-6 delivers explicit, systematic, highly scaffolded instruction that paves the way to grade-level proficiency.

Consumable student books provide access to complex grade-level social studies, science, and literary texts. Plus, Express! aligns with Benchmark Advance to boost language and knowledge acquisition with Core instruction.

Teach English through content with Express! Learn more at Benchmark Education dot com.

Dr. Jennifer Nigh: I want to revisit back to those students that are maybe older, let's say sixth grade, seventh grade, eighth grade, whatever the case may be, and they might be reading at a second-grade level, and they need those evidence-based practices to help them acquire literacy. Do you have any advice about how, though, you motivate those students? Because I know a lot of times the critique is, “Well, you know, they're bored reading these decodable texts” because you're trying to make sure that they're getting practice with the phonics skills that you just taught. So, any advice there about what you can do as an educator to support those students?

Nate Hansford: Yeah, definitely. And this is a topic I’ve spent, probably, a long time on.

Dr. Jennifer Nigh: Good, let's go for it, because I think it's really a pressing one! I hear it all the time!

Nate Hansford: Yeah, well, okay. So first off, this idea seems to go back to this debate between skill-based instruction and inquiry-based instruction all the time, as, “Well, skill-based instruction is boring.” And I would say, “Only if you make it boring.” And on the reverse hand—and I've been there, you know, I was a student who was in Ontario and we have to learn French as a second language—and I always really struggled in French class, and part of why, I was just really behind because I didn't pay attention very well. And then when I was trying to follow along with my classmates are reading French novels and I don't know the French alphabet, really—I know technically the letters are the same, but they make different sounds. It's very hard for you to catch up. You sort of just stare at the page and pretend you know what's going on, and then write random answers and guesses. That's not fun. That's super stressful and boring at the same time. It would be the same as throwing someone into an advanced math class and saying, just play with it, have fun with it, when you don't know anything about the topic. That doesn't make any sense from an understanding of science, of instruction in general. Personally, I use a lot of games, I love to use games in my classrooms. I have ever since I was teaching in Korea, and that's a big thing in Korea. But I use games to teach the skills that are important for helping students to develop those fundamental levels. Skill and drill works. You know, I often hear that phrase, “Drill and kill,” as if it's a bad thing.

Dr. Jennifer Nigh: (Laughter)It's been around a long time. Yep.

Nate Hansford: Right. As if all rote memorization is a bad thing, but rote memorization is there because it works. And there's actually a ton of research showing that. And that's because some students need multiple times in interacting with a piece of information to get it. You have kids who you might be able to teach them when “A” and “E” are together, “A” can make that “ay” sound. You might have some kids who only need to hear that once, and you might have some kids who need to hear that twenty times, who are still going to go “ah, eh” when they see “A” “E” next to each other.

Dr. Jennifer Nigh: I'm a monolingual, unfortunately. I wish I spoke another language. But that brings in that issue of cognitive load too. So that need for, especially, a language learner who is navigating their native language and trying to acquire a second language, that cognitive load is pretty intense. So giving them that repetition to really help limit that cognitive load so that they can get it more fluently is—

Nate Hansford: Yeah, absolutely. And I think taking those games down into those benchmark skills is really valuable and important. And it can go the other way, too. I'm not going to name the name, although there is an app that I’ve used as an adult to try and learn French, and I got really far with it, actually—the app claimed I was in the “millions of words” range. I don't know if it was true, but it claimed. But I started to find it very overwhelming because it taught through a whole-language approach. It didn't teach any phonics, and it didn't teach any grammar or spelling rules or any morphology. And I was able to memorize a lot of French words, but it really didn't help me much with pronunciation. And it didn't make me good at reading new French texts on my own. And once I got to the higher tiers, it actually started to become incredibly frustrating because I just couldn't keep up with the work anymore without having had previous that explicit instruction to go along with it.

Dr. Jennifer Nigh: Yeah, yeah. That's interesting. You brought up, bringing up the app—I'm curious, you know, going back to what you've learned about English Learners and what they need to acquire literacy and language, and that a lot of it is the same. But also using assessment in order to make sure that you are really supporting the student's needs. So another real challenge, and I'm not sure if this is as big of a challenge in Canada, but here in the States, we have a lot of teachers who haven't been trained or not equipped to support these language learners, because we have more language learners in places that they haven't historically been. It's good to hear that they can draw upon what they know or evidence-based practices in teaching literacy, but how can technology maybe help with this? Any thoughts about that?

Nate Hansford: Yeah, absolutely. I mean, ChatGPT, by the way, is a phenomenal tool for this situation, and I was a bit nervous about the impact ChatGPT would have on education. But I've ended up using it almost every day this year as a school teacher, and I actually am sold that the value for teaching, at least—I don't know about the value overall—but the value for teaching, at least, seems to be stronger than the possible cons, in my opinion. Because you can quickly, very quickly, translate instructions to students. And if you're going to give instructions to students and they're an EL learner, especially if they're a very new ELL learner, I think having those instructions in both languages is incredibly valuable. And actually, there's one other area there's a ton of research on, for ELL learning, is feedback. In fact, I think we have more research on feedback than anything else. And for whatever reason, we have pretty strong research suggesting that written feedback is more valuable to ELL students than oral feedback. And I would imagine that that's just maybe because when English isn't your first language, your processing speed, especially orally, is much slower. And personally, I know I can read French a lot better than I can listen to French. So having that written down, especially if you can have it down in multiple languages, is great. Especially, you can just translate whole texts very quickly.

Kevin Carlson: After the break: Some final thoughts from Nate Hansford. Stay with us.

Student voices in mid-roll: Kamusta. Hola. Hola. Hola. Hello. Konnichiwa.

Mid-roll announcer: As the English Learner population continues to grow, more and more Newcomer students are attending K through 12 schools.

Student voice in mid-roll: Where are you from?

Student voice in mid-roll: I'm from Haiti.

Mid-roll announcer: Newcomers face a number of integration barriers as they master a new language in a different educational system. Benchmark Hello! is a unique and comprehensive program that equips newcomers with essential oral language from Day One.

Student voice in mid-roll: Want to work on something together?

Student voice in mid-roll: Yeah, that sounds fun.

Mid-roll announcer: Meet the unique needs of Newcomers, accelerate their language development, and create an environment where Newcomers thrive, with Benchmark Hello!

Student voices in mid-roll: Bye! Adios! Bye! Bye!

Mid-roll announcer: Find out more about Hello at Benchmark Education dot com.

Dr. Jennifer Nigh: Do you have any of those other kind of tips that teachers can implement tomorrow to really support those English Learners that are acquiring literacy and language, especially that we know is grounded in research?

Nate Hansford: Yeah, definitely. Another one unrelated to feedback is just—there's been a lot of analysis on when we do feedback, there's three different ways we can give it: We can just tell the students the right answer; we can rephrase the question to try and get them to give us the right answer; or we can explain the rule behind the question and explain why they got the answer wrong. And that last one has been shown to be the more supportive form of instruction for students.

And I can also say that personally, that's the thing that I really struggled with when I tried to learn French via apps, is that once I got into the higher levels where there's multiple tenses, it got really easy to mix up those grammar rules and not have—in the app I was using, it would just tell you you got the answer wrong and tell you the correct answer, but it wouldn't tell you why your answer was wrong and why you should have put that correct answer. So you had to sort of piece that together on your own, and it almost felt like a bit of inquiry-based learning, and not in a good way.

I think similarly, there's some research suggesting that segmenting drills are specifically valuable for ELL learners, and I think that makes a lot of sense. And particularly it's supposed to help not only with spelling and comprehension and writing and listening, but also pronunciation, because when you do a segmenting drill, not only are you teaching how a word breaks down, not only are you teaching how our spelling system works, but you're also teaching students individual phonemes in the English language. And I know that's a thing that ELL students are going to struggle with. I know it from personal experience. I still struggle with all the sounds that exist in the French language. So providing that explicit instruction on what are these individual sounds and how do words break apart with them is really valuable.

Dr. Jennifer Nigh: Good, good. I know that you are passionate about digging into the meta-analysis to find out what works. What recommendations do you have for teachers who maybe are not doing that right now, but really want to know what works? How do they cut through all of this noise, and what advice do you have for them to really get to what works, without needing to dig into necessarily heavy research or meta analysis and all of those different types of things? What can they do to figure it out?

Nate Hansford: Yeah. I mean, there's lots of little things they can do. There's lots of meta-analyses in education that are open access that they can view, or at least results are available. So if they are interested about a particular topic, let's say a teacher trainer comes in and they say, “We're going to start this new thing, everybody's going to be doing collaborative inquiry, it's the best thing that has ever been invented for teaching, it's going to solve all your problems”—you can just go into Google, you can type “collaborative inquiry meta-analysis” and see what the researchers found. And the value of a meta analysis is that it's going to look at multiple studies at once. If you want to look a little deeper, there's a great website out there called Hattie Meta X (https://www.visiblelearningmetax.com/), and it keeps a summary of basically all education meta analyses that have ever been written, on all topics. It's an incredibly valuable website. It doesn't give a lot of context, so it'll just tell you the results, the name of the study, and the demographics. There's my website, which is free. It's Teaching by Science dot com (https://www.teachingbyscience.com/), or Pedagogy Nongrata dot Com (https://www.pedagogynongrata.com/). We had so many articles, we had to make a second website.

Dr. Jennifer Nigh: That’s a good problem to have, right? (laughter)

Nate Hansford: Yeah. We have a lot of articles on a lot of different topics, all focused on, “Well, what does meta-analysis show on this topic?”

And lastly, if you would like to spend your money, you can always check out my book The Scientific Principles of Teaching. Not only does it provide a summary of a large number of meta analyses on education, it also has several chapters devoted just to explaining this topic a little bit more and how to understand meta analysis as an everyday teacher.

Dr. Jennifer Nigh: Great. Those are great recommendations and great resources, so I appreciate you sharing those. And something you said very first is, if a trainer comes in or you're doing professional learning and… Google it. But you also said question it. And I think that's one of the things that a lot of new teachers, or maybe even experienced teachers—I knew it took me a long time in my career to feel comfortable that I should question it versus just assume that, “Oh, this is an expert telling me this, then this might be right”—but I think that we've obviously all learned that that's not always the case. So being confident to question the practice and dig a little bit deeper to say, “Is this truly something that is going to move the needle for my English learners and really all of my students?”

Nate Hansford: Yeah, I just think in general, that expert model doesn't really work in the sense that there's just millions of people out there claiming they're an expert in education and they don't all agree with each other, and then you're stuck just picking, “Well, who's my favorite?” I think a better way of looking at it is, “Who's presenting the most compelling evidence?” Don't worry about if you like them or if you like what they say, worry about what kind of evidence are they presenting and sort of the credibility that way.

Dr. Jennifer Nigh: Yeah. And I think that is wonderful final advice. I've learned a ton in our conversation and just really appreciate you questioning and digging deeper and helping educators all around the world.

Nate Hansford: Thank you very much for having me on your podcast. I enjoyed our chat today.

Dr. Jennifer Nigh: Great. Thank you so much, Nate. Much appreciated.

Kevin Carlson: Thank you, Nate Hansford. Thank you, Jen Nigh. And thank you for listening to Teachers Talk Shop.

In this episode, you heard Nate and Jen discuss meta-analysis of English Learners, along with some techniques to help those learners that you can bring into your classroom right away. To implement these evidence-based techniques, you need high quality instructional materials. Benchmark Education can help you put research into practice with materials designed for English Learners at any level of language proficiency. Benchmark offers programs that engage minds, elevate achievement, and empower every learner. Visit Benchmark Education dot com today to get started.

For Benchmark Education, I'm Kevin Carlson.