- Benchmark Education

- Newmark Learning

- Reycraft Books

- Create an Account

Interactive Writing: Intentional Decision Making to Teach Foundational Skills

by C.C. Bates, Ph.D.

Decisions, Decisions…

It has been said that as teachers we make about 1,500 decisions a day. Thinking about this may cause us to feel a little overwhelmed at first, but when we ground decisions in our understanding of what our students know and control, and apply this knowledge to effective instructional practices, decisions become intentional and productive.

During interactive writing, teacher and students negotiate and create a text. The term interactive in interactive writing refers to students’ participation in both the creation and writing of the text, but I also like to think about what the term interactive means from a teaching perspective. For me as a teacher, the term interactive captures the synergy between my students, the grade level expectations, and the affordances of the text. The unique interaction among these factors contributes to the in-the-moment decisions I make to support my students.

Foundational Skills

Interactive writing is almost like one-stop shopping, as every foundational skill relevant to students’ reading and writing is contained in the practice. These are the key skills:

-

Print Concepts – During interactive writing, students see how text follows a left to right, top to bottom format. Interactive writing clearly demonstrates how the stream of speech is broken up by words (also a phonological understanding) on the page and how these words are separated by space, further highlighting one-to-one correspondence or voice-to-print match.

-

Phonological and Phonemic Awareness – During interactive writing, students map spoken language to its written form. As this process unfolds, children can count the words they hear within a sentence, listen for the number of syllables in a word by clapping its parts, and break words into onset and rime. They can also engage in phonemic analysis by slowly articulating a word to segment and identify each individual sound or phoneme.

-

Alphabetic Understandings – During interactive writing, students develop alphabetic knowledge which includes the ability to recognize and name letters, connect letters with their associated sound(s), and efficiently form letters. To truly develop letter fluency, all these aspects must be known.

-

Phonics & Decoding – During interactive writing, the co-constructed text is created word by word. As each word is written, teachers demonstrate how the sounds within a word are connected to the representative letters. For example, when saying the word night slowly, we identify 3 phonemes /n/ /`i/ /t/. Interactive writing maps these phonemes on to the letters that represent the sounds, so students see that “long i” is represented by the grapheme “igh.” Repeated exposure through both writing and reading solidifies “igh” as a unit and contributes to decoding similar words like light, bright, and frighten.

-

High-Frequency Words – During interactive writing, students encounter many of the most commonly used words in the English language. Repeated exposure to the letter-sound connections in these words helps them become stored in long-term memory so they can be automatically retrieved.

Differentiating Instruction

The development of students’ foundational skills is unique. Using interactive writing to supplement a core language arts program provides additional opportunities for students to apply those foundational skills when writing and reading continuous text. We know students’ literacy development doesn’t always follow the timeline provided in the teacher’s guide, but through interactive writing we are able to differentiate instruction to meet the needs of all students, regardless of where they are in their literacy acquisition. That means that during this 10–30-minute period, I am making a number of decisions, but the decisions are easy because I take into account my students’ strengths and needs, the grade-level expectations, and the opportunities the text presents.

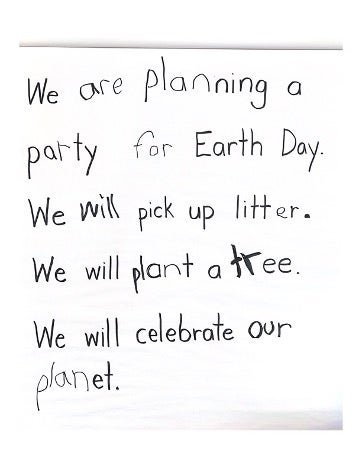

Consider the following text:

First, think about your students and your grade-level expectations. Then connect these thoughts to the text. What opportunities do you see in the text? Based on your students, the expectations, and the affordances of text, what in-the-moment decisions would you make? Which students would you call to the chart to capitalize on these opportunities?

The Students, The Expectations, The Text

This Earth Day text was created by students in a first-grade class. Because interactive writing texts are also used for shared writing, it is important that as they are created, we consider their readability. For example, after the gist of the text is established through a constructive discussion with the students, I gently mold the ideas and language the students have shared to create a readable text. This is done in cooperation with the students and is best accomplished using a sentence-by-sentence approach. As seen in the text shown above, we decided to write, “We are planning a party for Earth Day.” Once the first sentence was written, we moved onto the next sentence, “We will pick up litter.” Then, “We will plant a tree.” And finally, “We will celebrate our planet.” Interactive writing doesn’t mean that every word must be written by a student, and this is where decision making takes center stage.

Depending on the amount of time allocated for interactive writing, we may finish writing the text or come back to it later. Regardless, as the text is created, I am thinking about the affordances of each sentence and then selecting the most productive and generative examples to highlight. For example, if a child hasn’t yet grasped the understanding of word boundaries, I may decide to call that student up to the chart to provide a two-finger space as I start the next word.

In the Earth Day text, I chose to highlight r-controlled vowels and plan in the words planning, plant, and planet. Writing and reading are reciprocal processes and after we were finished writing the text, we went back to these three words and talked about the importance of reading all the way through each of them. I also selected a few high frequency words for students to write: for, will, and our. These words all contain units (or, ill, and ou) that support generative word solving and being able to write and read these words is beneficial. Additionally, I chose to emphasize /tr/ as the sound is often confused with /ch/. Finally, we clapped the syllables in celebration and explicitly linked each syllable to the representative letter(s). As the text was written, other words were slowly articulated to emphasize important phoneme-grapheme correspondences. Of course, this work was all embedded in an authentic and meaningful text, which we revisited for shared reading over the course of the week

In Closing

As with any instructional practice, it is important to establish supportive routines and have materials organized and ready for use. Figuring out the elements related to managing interactive writing allows us as educators to fully focus on making intentional instructional decisions.

What Next?

What are we learning about how children learn to read? And how does that inform our instructional practices and accelerate student learning? Join author C.C. Bates and Patty McGee as they discuss where theory meets practice in the literacy classroom—only on the Teachers Talk Shop Podcast! Listen Now →

About the Author

|

C.C. Bates, Ph.D., is an Associate Professor in Literacy Education at Clemson University in South Carolina. C.C. has a Ph.D. from Georgia State University in Language and Literacy, and she is a former classroom teacher and reading interventionist. She is also the author of Interactive Writing: Developing Readers Through Writing. |

You May Like: Interactive Writing: Developing Readers Through Writing

Comments